Back Basa Zaza ACE Zazaki Afrikaans Zaza-Sprache ALS ዛዛኪኛ Amharic Idioma zazaqui AN اللغة الزازاكية Arabic لغه زازاكي ARZ Idioma zazaki AST Zaza dili Azerbaijani زازا دیلی AZB

| Zaza | ||

|---|---|---|

| Zazakî / Kirmanckî / Kirdkî / Dimilkî | ||

| Native to | Turkey | |

| Region | Provinces of Sivas, Tunceli, Bingöl, Erzurum, Erzincan, Elazığ, Muş, Malatya,[1] Adıyaman and Diyarbakır[1] | |

| Ethnicity | Zazas | |

Native speakers | 3–4 million (2009)[1] | |

| Dialects |

| |

| Latin script | ||

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-2 | zza | |

| ISO 639-3 | zza – inclusive codeIndividual codes: kiu – Kirmanjki (Northern Zaza)diq – Dimli (Southern Zaza) | |

| Glottolog | zaza1246 | |

| ELP | Dimli | |

| Linguasphere | 58-AAA-ba | |

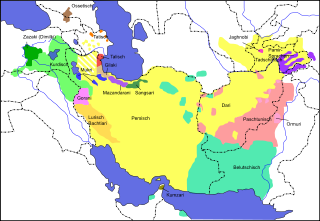

The position of Zazaki among Iranian languages[4]

| ||

Zaza is classified as Vulnerable by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | ||

Zaza or Zazaki[5] (Zazaki: Zazakî, Kirmanckî, Kirdkî, Dimilkî)[a][6] is a Northwestern Iranian language spoken primarily in eastern Turkey by the Zazas, who are commonly considered as Kurds, and in many cases identify as such.[7][8][9] The language is a part of the Zaza–Gorani language group of the northwestern group of the Iranian branch. The glossonym Zaza originated as a pejorative[10] and many Zazas call their language Dimlî.[11]

According to Ethnologue, Zaza is spoken by around three to four million people.[1] Nevins, however, puts the number of Zaza speakers between two and three million.[12] Ethnologue also states that Zaza is threatened as the language is decreasing due to losing speakers, and that many are shifting to Turkish, as well as mentioning that there are a few monolingual speakers mostly the elderly. This is causing a decline as the language is increasingly not being passed down to younger generations, with most choosing to speak Turkish. Some also speak Kurmanji.[1]

- ^ a b c d e f Zaza at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

Kirmanjki (Northern Zaza) at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

Dimli (Southern Zaza) at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

- ^ "Multitree | The LINGUIST List". linguistlist.org. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- ^ "Glottolog 4.5 - Zaza". glottolog.org. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- ^ "worldhistory". titus.fkidg1.uni-frankfurt.de. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ Kenstowicz, Michael J. (2004). Studies in Zazaki Grammar. MITWPL.

- ^ Lezgîn, Roşan (26 August 2009). "Kirmanckî, Kirdkî, Dimilkî, Zazakî". Zazaki.net (in Zazaki). Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- ^ Michiel Leezenberg (1993). "Gorani Influence on Central Kurdish: Substratum or Prestige Borrowing?" (PDF). ILLC - Department of Philosophy, University of Amsterdam.

- ^ "Minority Rights Group International (MRG)-Minorities-Kurds".

- ^ Kreyenbroek, Philip G.; Sperl, Stefan (7 May 2015). The Kurds: A Contemporary Overview. Routledge. ISBN 9781138869745.

- ^ Arakelova, Victoria (1999). "The Zaza People as a New Ethno-Political Factor in the Region". Iran & the Caucasus. 3/4: 397–408. doi:10.1163/157338499X00335. JSTOR 4030804.

- ^ Asatrian, Garnik (1995). "DIMLĪ". Encyclopedia Iranica. VI. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ Anand, Pranav; Nevins, Andrew (2004). "Shifty Operators in Changing Contexts". In Young, Robert B. (ed.). Proceedings of the 14th Semantics and Linguistic Theory Conference held May 14–16, 2004, at Northwestern University. Vol. 14. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University. p. 36. doi:10.3765/salt.v14i0.2913.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help)

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search